The Horror – Face to Face With the Tragic Chapter of Cambodia’s Recent History

“One evening, I saw a 16-year-old guard walk in my room. He then approached an old man who was sleeping opposite me. He stamped on the chest of that old man again and again. I did not know why he did so or what was wrong with that old man. I heard that old man groaning as his mouth bled. No one was able to help anyone else.”

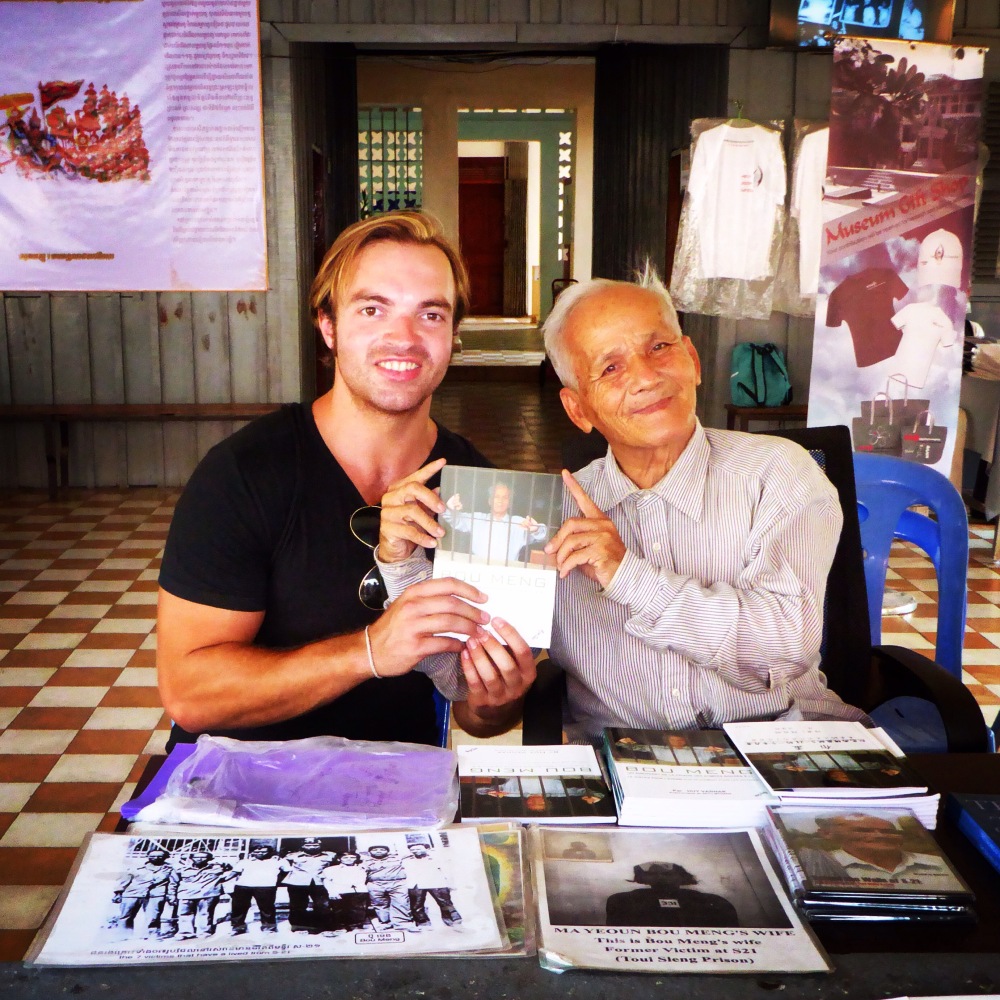

This is, believe it or not, one of the tamer excepts from the memoir of Buo Meng, a survivor of the Khmer Rouge S-21 torture prison in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

For four years, 1975-1979, Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge regime inflicted one of the worst genocides ever seen on this planet in the small Asian nation of Cambodia.

The horror described by Buo Meng of what he saw from his time in prison is just a small part of the widespread human devastation.

At the Chong Euk killing fields just outside the capital, a memorial stupa stands in the middle filled with human skulls piled high – a fraction of the victims who died at the whim of the regime.

Walking around the fields and listening to stories of what occurred there brought on severe anguish and nausea. “Why, why, why” I kept repeating my head, getting more exasperated.

I was reminded of my similar feelings when I visited Auschwitz more than ten years ago now. There I thought I would never come close to seeing such a grim stage for man’s inhumanity to man.

But history repeats itself around the world at an alarming rate.

The Soviet Union, China, Burundi, Bosnia, the Congo et al.

Bone fragments can still be seen in the mud as one walks around Chong Euk. Bits of clothes stick out of the ground where once hundreds and thousands of bodies were dumped on top of one another, left to rot.

The foul stench lingered for miles.

It’s something that one cannot comprehend from reading about it in a history book at school. It almost seems other worldly, as if in a distant universe where lives don’t matter as much.

But they do. And you only have to speak to almost any Cambodian to hear how the genocide affected their family. Indeed, most of the population is under 40, such was the scale of the horror.

Blood still stains the floor of the Tuol Sleng S-21 torture prison. Thousands were held captive there, forced in tight cells with many others with a communal bucket and bottle as their bathroom. If they didn’t die there, most inmates were sent to the killing fields to meet their fate. As soon as they were arrested they were photographed, and their pictures are on the walls of the prison now like ghosts frozen in stone.

Their crimes? What crimes. This was not a purge of enemies of the state, this was simply a purge of the people. Crimes were fabricated and people signed fake confessions in the vain hope that the brutality would come to an end. Beatings, water torture, electrical shocks, hangings and so on.

What hope then that history will not come round again in such horrifying fashion? Justice still evades most of those responsible. Pol Pot never answered for his crimes, dying in 1998 before he could trial.

Even those who are in court now at the UN assisted Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (Khmer Rouge tribunal) are using every bit of red tape their lawyers can muster to essentially see out their lives before ever facing a sentence.

Some still stand by their actions. In what world I cannot fathom. Just as I could not and still cannot comprehend the willingness of the Nazi’s to enforce such hatred, so I despair at the inability to understand what warped mind would be capable of inflicting gruesome pain and suffering on another human being.

Buo Meng sits in the S-21 museum now selling his book and smiling with foreign visitors. He is one of seven survivors of the prison, and he has continued his life. To have half his strength, would make many very resilient individuals.

In his book, he recalls how he and his wife worked for the revolution believing they were fighting for a brighter future. On the day they were both arrested, Buo and his wife were separated. He never saw her again.

“There was no single day that I did not shed tears. I endured much pain. I wished I would die soon so that I would not continue to suffer. My life was so miserable.”

The most haunting part of the visit at Chong Euk was when we came to a large and distorted tree. It was then we were told this tree was used for smashing babies and children against.

No words can express the feelings I experienced upon learning that ghastly fact and staring at that very tree. It is something that will haunt me forever.

But something I did feel was a strong sense of hate. I was raging inside at the memory of those perpetrators. Clenching my fists I screamed silently in anger at them, wishing their end was infinitely more painful than those of the innocent.

And then I realised – that was part of the problem.